https://karachilajamia.com/

In their video work Jinnah Avenue, (2017), Shahana Rajani and Zahra Malkani, who together form the artist duo and “anti-institution” Karachi LaJamia, ask a rhetorical question: “Did the colonial dream of a road materialize?” Alluding to the British, Portuguese, and Dutch colonial systems’ focus on discovering routes and building roads and railways to previously “undiscovered” areas populated by “uncivilized” peoples, Jinnah Avenue scrutinizes the local governments in Karachi, Pakistan that have perpetuated these same notions in the name of “development.”

The video homes in on the infrastructure of Gadap Town, a neighborhood in northwest Karachi whose land has been subjected to rapid, destructive consumption, and whose indigenous communities have been displaced and subject to police violence. Rajana and Malkani use the fourteen-kilometer thoroughfare Jinnah Avenue as an indicator of how nation states wield control through land ownership, urban “renewal,” and surveillance. They position the road as a “technology of erasure,” demonstrating how neocolonial powers have shaped public infrastructure to rub out the ecologies and indigenous histories of Karachi. Through industrial development, unsustainable energy generation, and the consequent pollution of the air and water, the colonial dream of a road has indeed materialized in the city. Karachi LaJamia’s work situates itself within this urban landscape, surveying a paradigm that was initiated by the British and perpetuated by successive local governments, each desiring more and more infrastructure to keep up with the colonial priorities of land-grabbing, profiteering, and maintaining sovereignty.

In 2015, two years before Rajani and Malkani made Jinnah Avenue, the artists founded Karachi LaJamia, originally named the “Karachi Art Anti-University.” As products of the conventional academic institutions of Karachi and abroad, Rajani and Malkani wanted to question the systems that had shaped them. Ten years later, Karachi LaJamia’s body of work now includes collaborative research projects, essays, site-specific courses and curricula, multimedia installations, web archives, and activity books for children. All are thematically aligned with understanding the city and its public spaces as sites of study, research, discussion, and the production and dissemination of knowledge. Karachi LaJamia’s practice remains staunchly anti-institutional; it is “a nomadic space moving outside the institution to collectively explore radical pedagogies and art practices,” in its own words. Their practice enacts a crucial, unique form of new institutionalism that centers equality, resistance, agency, and change, aiming to forge a path towards large-scale transformation within urban ecologies. Rajani and Malkani actively work towards dismantling the concept and languages of power in Karachi through their engagements with natural environments and non-hierarchical methods of building and disseminating knowledge.

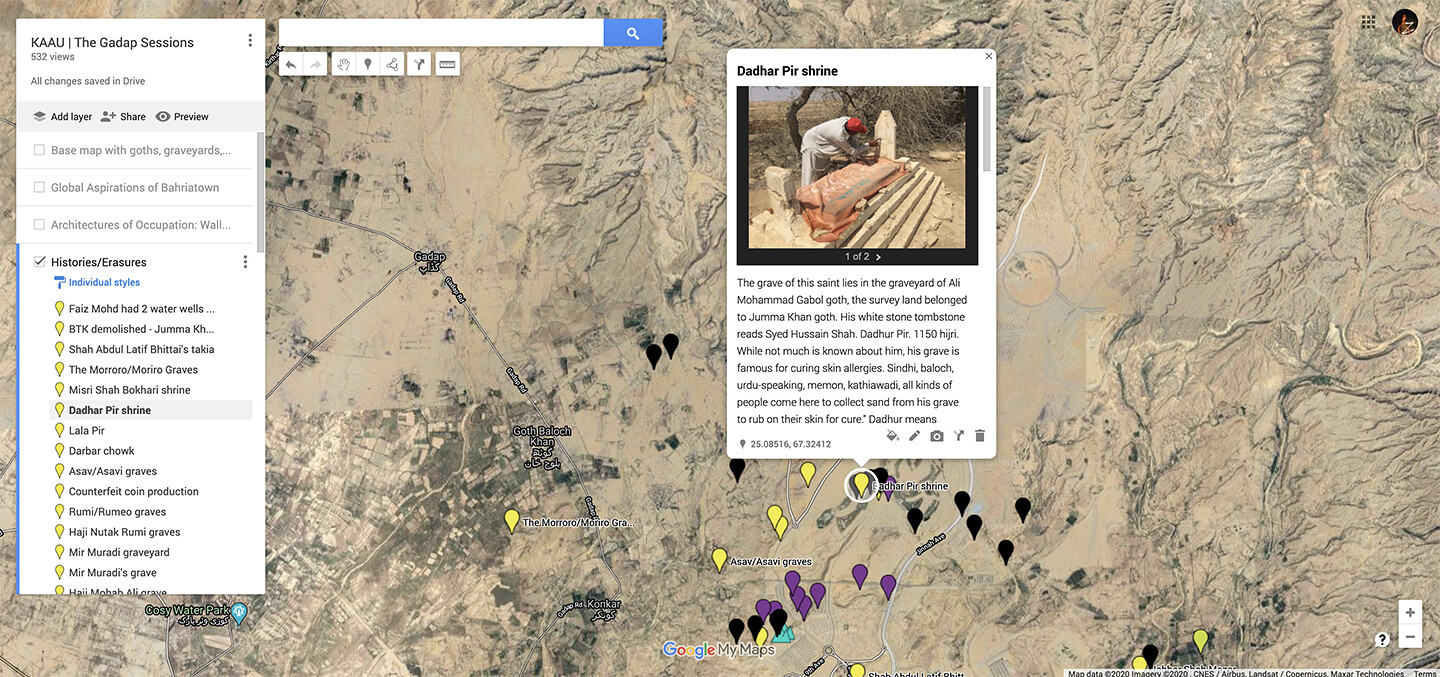

Karachi LaJamia put these cooperative, egalitarian methodologies into practice not long after its formation. Their 2016 course The Gadap Sessions, geared towards artists and researchers, was conducted in collaboration with the Karachi Indigenous Rights Alliance. The Gadap Sessions brought together thirteen participants, employing visual research methods to document how Karachi has evolved over time; the course placed emphasis on the city’s commercial and industrial development, its militarization, and the effects of climate change, particularly on indigenous communities. One case study examined Bahria Town Karachi, a 46,000-acre gated residential community—the largest of its kind in Pakistan—on the northeastern outskirts of the city. Since its opening in 2014, Bahria Town Karachi has encroached on lands that have been inhabited and farmed by indigenous Sindh and Baloch communities for centuries. Its developers have ignored these communities’ concerns and objections, even informing villagers that the supreme court of Pakistan granted the real estate company permission to seize their lands.1 The planned community has also devastated important habitats for migratory birds and countless other native species of flora and fauna.

Aerial view of construction progress on the Grand Jamia Mosque and surrounding housing complexes, Bahria Town Karachi, Karachi, Pakistan. © Pakistan Property Leaders.

A mapping project created by participants in Karachi Lajamia’s course The Gadap Sessions, compiling the locations of shrines, graves, and other sites near Gadap Town that are either endangered or have been destroyed by planned developments in the area. Courtesy of Karachi LaJamia.

Rajani and Malkani commenced the case study at a time when local citizens had been left in the dark about the private conglomerate Bahria Town Group’s plans for developing a golf club, an amusement park, high-rise apartments, and a fully equipped sports stadium. While one could very well perceive these facilities as having positive effects on many Pakistanis’ quality of life, Karachi LaJamia underscored how the project continues to perpetuate centuries of structural violence against and erasure of indigenous populations of the city by enacting policies of discrimination and displacement, privileging the interests of higher-income residents while further disenfranchising its poorer populations.

During The Gadap Sessions, Karachi LaJamia equipped participants with methodologies to document Bahria Town and beyond in Karachi—to archive and remember what the region was like before 2014, when ground was broken on what became the largest privately-owned residential community in Pakistan. The group ended up drawing a landscape from memory, illustrating state-promoted initiatives of violence, erasure, colonization, resource extraction, uneven development and displacement, climate change, and environmental degradation. Collected sounds, music, drawn maps, digital maps via Google and other tools, and photography were used to complement this landscape of remembrance. The Gadap Sessions prepared participants to recognize that their own neighborhoods could also be subject to state sanctions and, given Pakistan’s troubled colonial history and the 1947 Partition, even destruction.

Karachi LaJamia further resists languages of power through their curricula, which use contemporary art as an educational tool to facilitate rethinking and reimagining ecologies in Karachi. Two experimental publications, Exhausted Geographies vols. I and II (2015 and 2018, published in collaboration with Abeera Kamran), borrow from the scholar Irit Rogoff’s proposition that the geographical border is the most restrictive tool of the nation state.2 The Exhausted Geographies publications revisit public spaces and structures, such as Jinnah Avenue, various railway remnants, and bodies of water that have been depleted post-Partition. For example, wide-scale industrial activities along Karachi’s 135-kilometer coastline have contaminated the city’s drinking water with dangerous levels of lead, chromium, and other toxic substances, causing kidney-related diseases, anemia, and brain damage in its human population. Karachi’s residents also breathe heavily polluted air, a concoction, according to Pakistan Today, consisting of “transport and industrial emissions followed by burning of garbage, emissions from refrigerators, generators, flying of dust, and stoves used in houses and hotels.”3 While legal and legislative action has been taken against the relevant municipal governments, and though certain emissions regulations have been enacted, citizens’ lives remain in danger.

In 2021, Rajani and Malkani started actively translating their knowledge of this urban landscape into a series of courses titled Hamare Siyal Rishte (Our Watery Relations). Taking participants on a tour of the constantly evolving landscapes around the Indus (or Sindhu) river that winds through Karachi, Rajani and Malkani emphasized aspects of the land that cannot be seen on traditional maps—the area’s folklore and myths, its ancient river deities, its traditional songs. Hamare Siyal Rishte also uses sensory reflections, music, and meditation, orchestrated in partnership with organizations such as the Pakistan Fisherfolk Forum and Sindh Indigenous Rights Alliance. In their essay “Notes toward a Karachi Ecopedagogy: Sensing the Ephemeral Rivers,” Rajani and Malkani describe this pedagogical approach as an attempt to answer the following questions:

Where are we in relation to nature? What is this ground that holds us? Who walked it before us? Where does our food come from? Who grows it and under what conditions? Where does our concrete come from? Where does our water come from? Who fights for it? How can we visualize Karachi and ourselves within these webs of relationality that sustain us and that we systematically deny, desecrate, and devour?4

This strategy requires participants to return to their roots and existence in connection with the fragility of the waters of Karachi, which can be a difficult exercise in a land under neocolonial rule and riddled with conflict, heavy military operations, surveillance, and development mechanisms that prioritize the nation state over the individual. Rajani and Malkani rely on the ephemeral qualities of Karachi’s environmental ecosystem as pedagogical tools to exemplify resistance against state machinery of control.

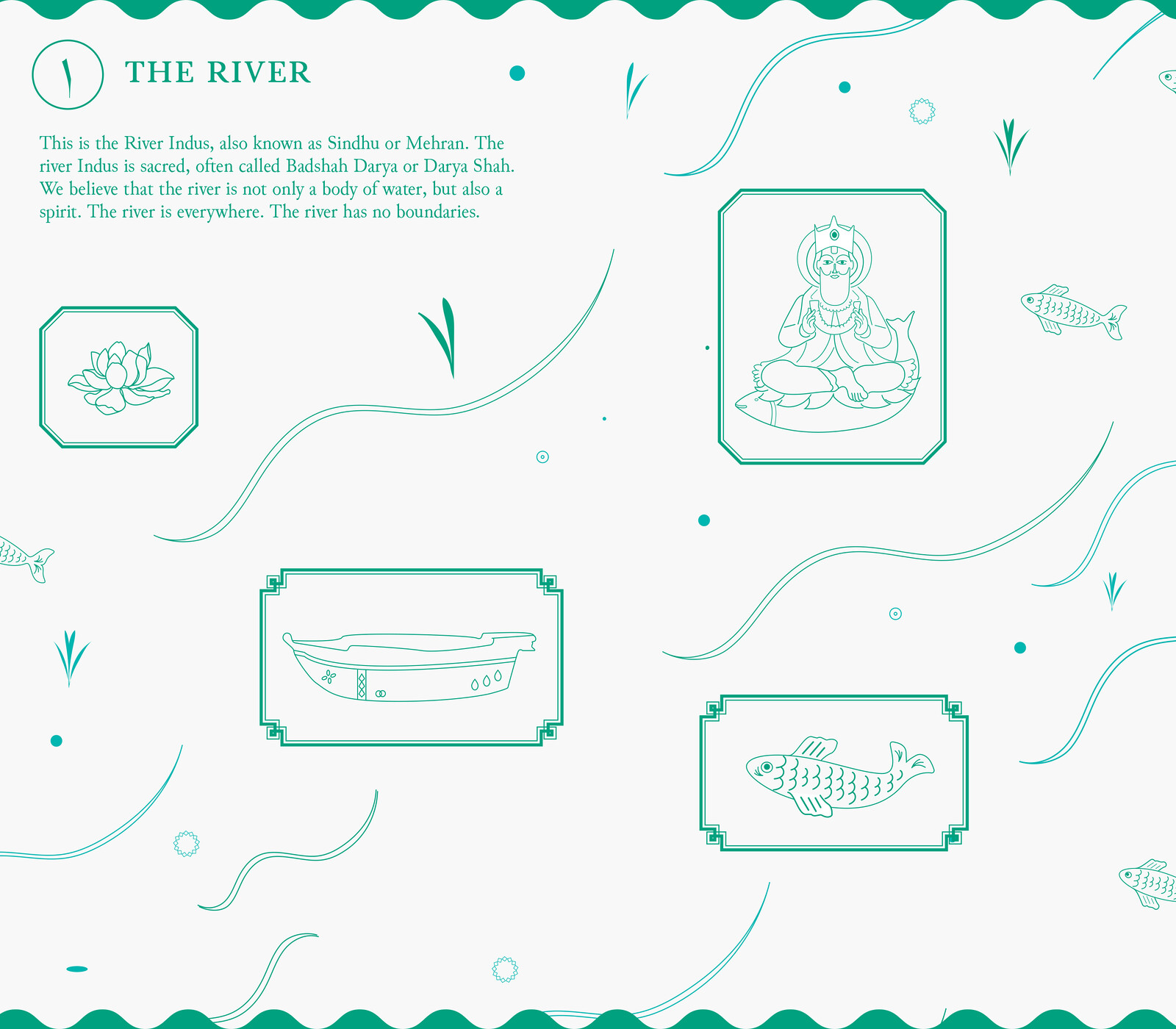

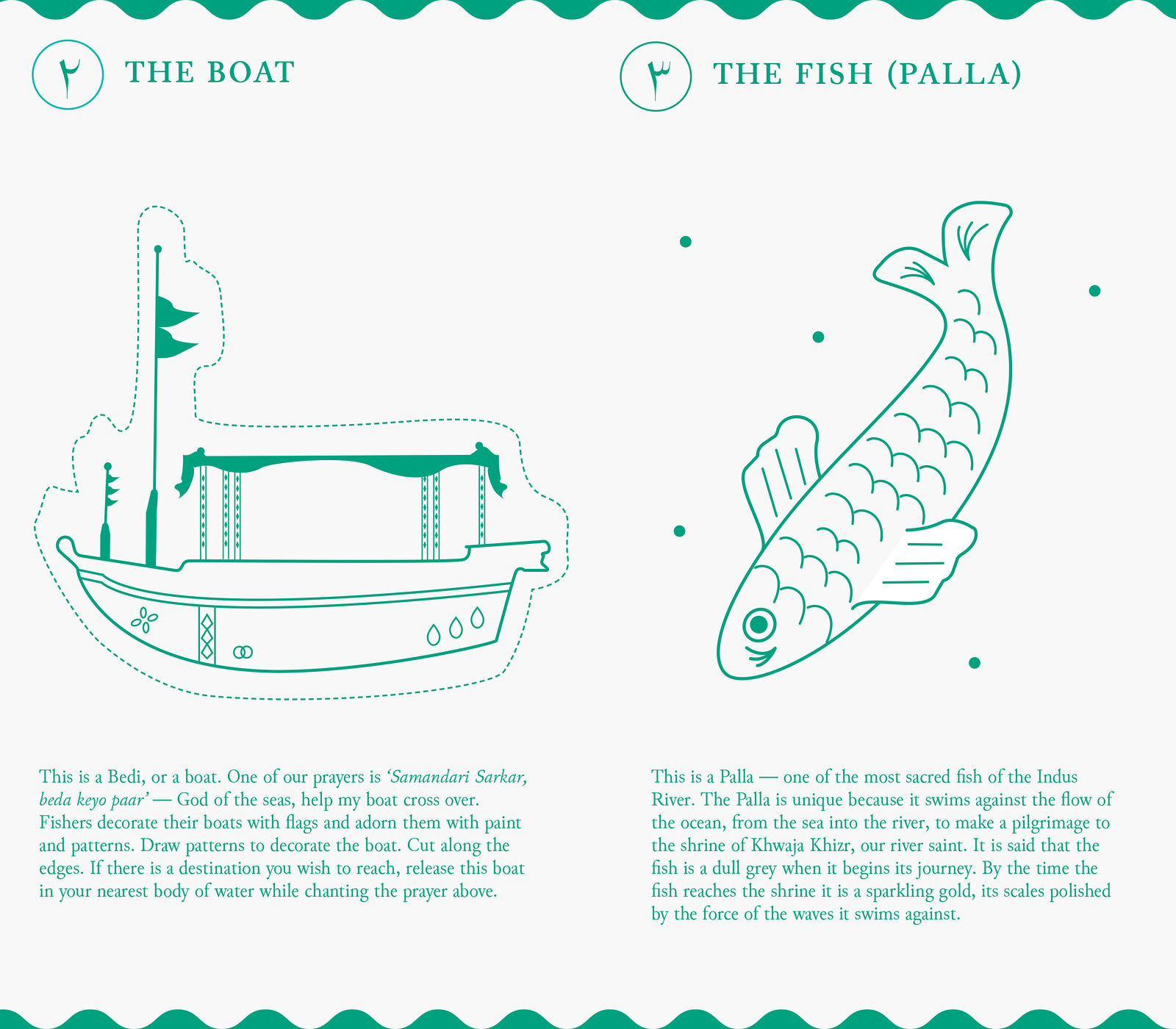

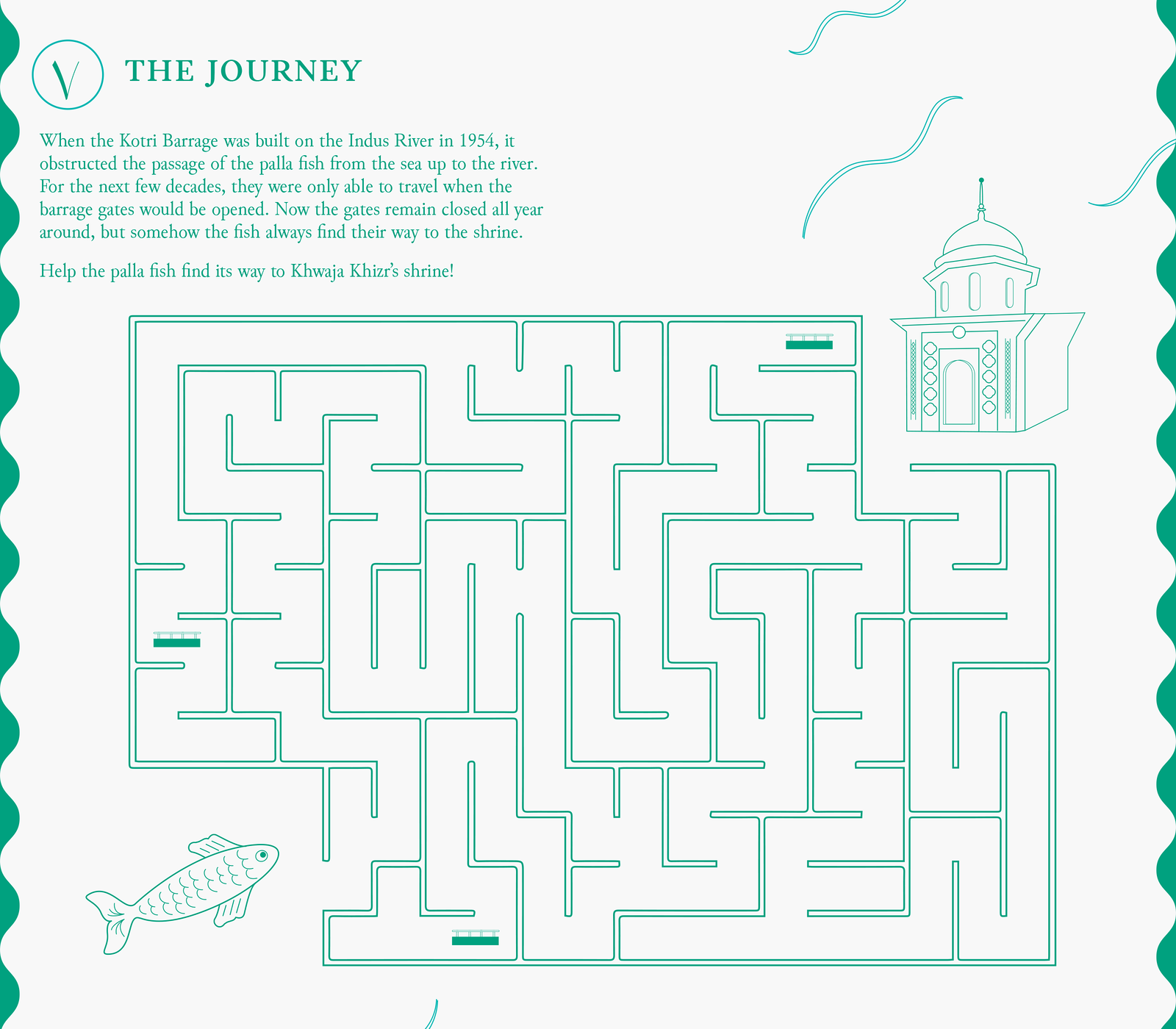

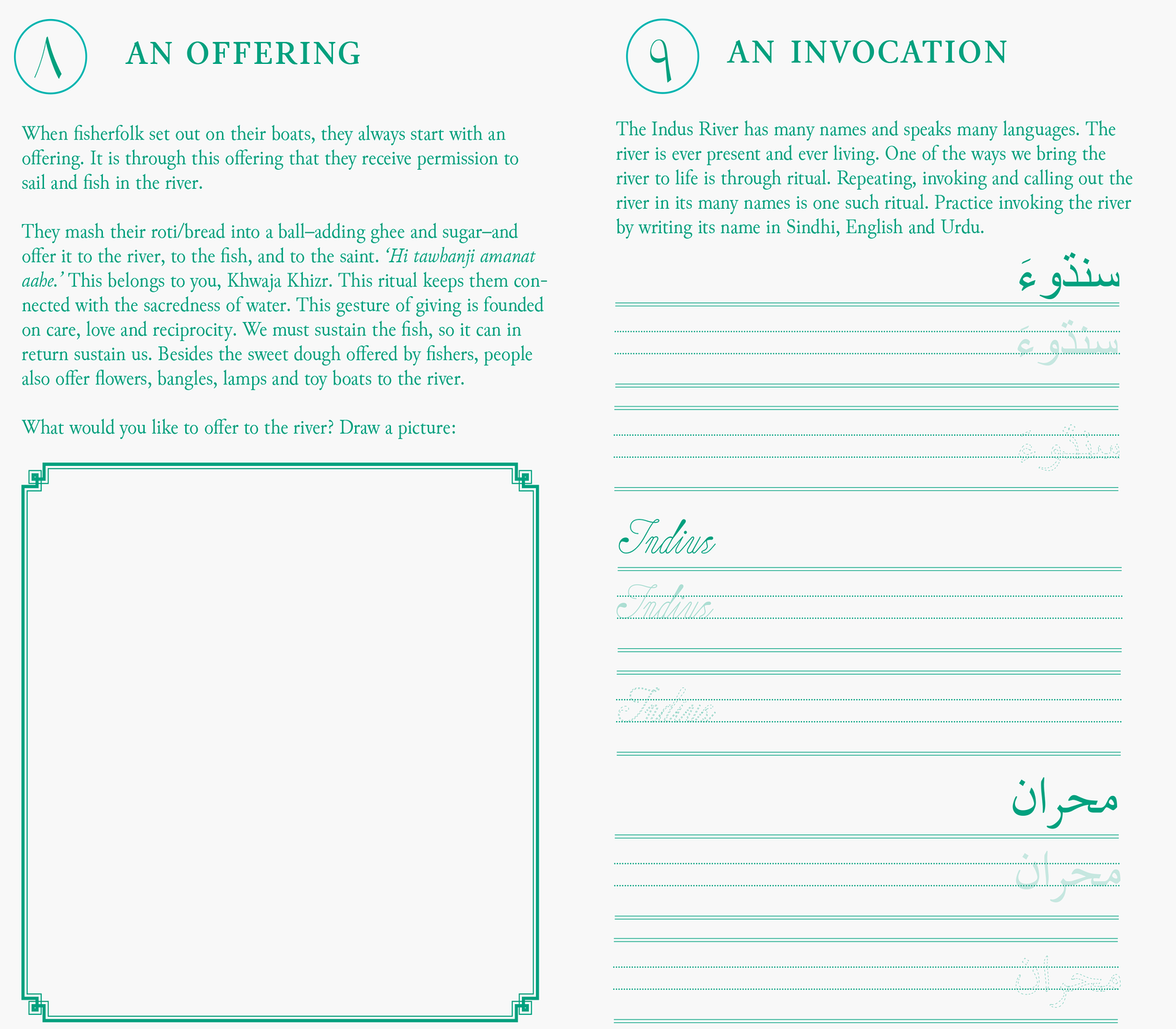

Spreads from an activity book made by Karachi LaJamia as part of their initiative Hamare Siyal Rishte (Our Watery Relations). Designed by Rose Nordin. Produced for the exhibition Stepping Softly on the Earth, Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead, UK, 2023–2024.

Spreads from an activity book made by Karachi LaJamia as part of their initiative Hamare Siyal Rishte (Our Watery Relations). Designed by Rose Nordin. Produced for the exhibition Stepping Softly on the Earth, Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead, UK, 2023–2024.

The latest Hamare Siyal Rishte venture entails crafting activity books that encourage children to experience and understand the ephemerality of the Indus River. One activity book introduces several elements that have defined the river’s spirit over centuries: boats named bedi, Palla fish that swims against the current of the ocean, lotus flowers that are used as offerings in acts of worship, lotus roots that are used in regional dishes, and Jhoolay Lal, the patron saint of the river, who is a beloved Avtar that sits on a lotus carried by a Palla fish. The activity book then asks children to reflect on these elements by imitating the journey a Palla fish would take to the shrine associated with Jhoolay Lal, resisting barrage gates that disrupt the natural flow of water. Upon reaching the shrine, an offering of their own is to be made to the river along with an invocation in Sindhi, English, and Urdu—three of the languages spoken in Karachi. These activity books are not mere didactics the children would usually receive in the formal education system of Pakistan. They are Karachi LaJamia’s way of orienting a new generation to the “watery relations” of Karachi, in turn giving them the knowledge and tools to resist the vast state infrastructure that does not pay enough attention to such relations. Rajani and Malkani encourage children to ask whether these ephemeral qualities of the Indus River are salvageable and in what ways. How can children remember Jhoolay Lal as they open their tablets every day at home and school? In what ways can they organize at grassroots levels at school to spread awareness about access to clean water?

Rajani and Malkani demonstrate the myriad shapes ecopedagogy can take as they teach others to act, remember, resist, and break down structures of power. Karachi LaJamia’s amphibious presence within the art world arenas of biennales, festivals, and galleries often manifests as presentations of its archives—projects such as lesson plans and reading resources of The Gadap Sessions, Exhausted Geographies, and Hamare Siyal Rishte, combined with video installations of Jinnah Avenue and other video works. This non-hierarchical model of praxis, pedagogy, and artmaking ensures that audiences of all ages, backgrounds, and communities can encounter the duo’s work, giving city dwellers a moment to pause and reflect on the changes to our own respective worlds. Cultivating knowledge and criticality in this fashion spreads and endures beyond the hasty, narrow, and exclusionary imaginary of neocolonial powers worldwide.

When I first encountered their work in my hometown of Colombo, Sri Lanka, in 2024, I found myself pondering the transitions that my own city has gone through in my lifetime: areas beset by civil war emergencies between the 1980s and 2000s have now developed into exemplars of rapid, postwar urban buildout. High-rise apartment complexes have sprung up, taking advantage of Colombo’s proximity to Sri Lanka’s commercial districts. In my past and present neighborhoods, conglomerates have been routinely buying up centuries-old houses and converting them into hotels, restaurants, and commercial buildings. The urban landscapes of developing countries in South Asia will continue to evolve under neocolonial systems, and Karachi LaJamia’s praxis invigorates their participants to think about our local and indigenous histories and ecologies that may be forgotten amid such rapid change.

Shah Meer Baloch, “‘They fired at everyone’: peril of Pakistani villagers protesting giant luxury estate,” Guardian, May 28, 2021

Irit Rogoff, “Exhausted Geographies,” (lecture, University College London, March 2013), →.

“Karachi world’s fourth largest polluted city: report,” Pakistan Today, February 8, 2022, →

Shahana Rajani and Zahra Malkani, “Notes toward a Karachi Ecopedagogy: Sensing the Ephemeral Rivers,” Anthropocene Curriculum, February 7, 2022, →.