In a photograph, two chairs, draped in white cloth, stand sentry around a rubble heap—old fences, shutters, doors. The chairs belong to the Ebrahim family. In 1981, the Apartheid government forcibly evicted the Ebrahims from their home, Manley Villa—one of the last to be demolished in District Six, a historically multiracial community in Cape Town that had been declared a “whites-only area” in 1966. Sue Williamson’s exhibition at the city’s Gowlett Gallery, “The Last Supper,” displayed detritus the artist (who is white) had collected from the demolition sites (prompting a visit to the show by police). That detritus is gone now, though photographs of the exhibition remain. Photographs and, miraculously, these chairs.

The chairs feature prominently in a new installation called Don’t let the sun catch you crying, created for Williamson’s first major retrospective, curated by Andrew Lamprecht. Nearby, former District Six residents and their descendants are captured in a series of photographs, enjoying a meal of cupcakes and cool drinks in the brush where the neighborhood once stood. Despite a 2018 Land Claims Court ruling that ordered the government to address land restitution claims, District Six remains largely undeveloped. The community continues to fight for the right to return home.

In many ways, this retrospective serves not only as a survey of Williamson’s career but as a repository of South African social history over the past five decades. Take R.I.P. Annie Silinga. Williamson photographed the activist in 1982 as a part of “A Few South Africans,” a series of portraits of women whose role in the liberation struggle had been overlooked, of which postcard versions were distributed widely. In 1984, when Silinga passed, Williamson was tasked with screen printing T-shirts to be worn at her funeral. A decade later, with the family’s blessing, she created a grave cradle for Silinga, which was exhibited at the first Johannesburg Biennale before being installed at the gravesite. Some years later, the cradle was stolen and, probably, sold as scrap metal.

This is an unusual life cycle for an artwork—from biennale to graveyard to scrap heap—but it is one that speaks volumes about South Africa’s thorny transition from racist authoritarianism to neoliberal democracy. That first portrait circulated Silinga’s image in defiance of a state that sought to repress it; the grave cradle was made in the wake of the first democratic elections and South Africa’s renewed visibility in the art world following the cultural boycotts; its disappearance signaled the nation’s failure to meaningfully redress the economic inequality that persists as a hangover of colonialism and apartheid. The piece has been remade for this retrospective, decorated with paper flowers encased in glass domes and etched with Silinga’s defiant phrase, “I will never carry a pass.”1

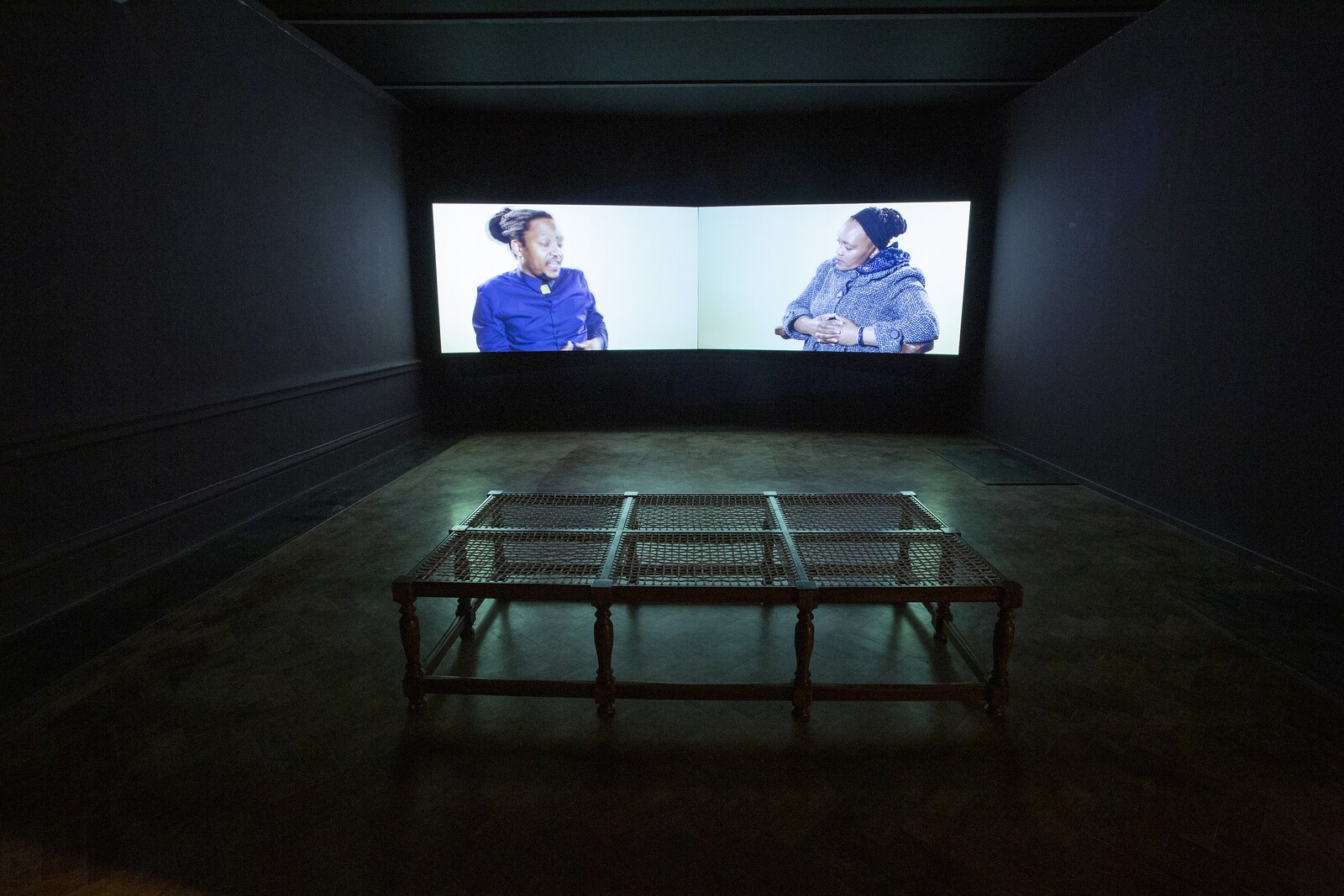

Documentation, circulation, and memorial have long been the pillars of Williamson’s practice, which has always straddled activism and the art world. Williamson’s dream was to be a journalist, and photographs, photocopies, interviews are the methods and media to which she has regularly returned. The video work from which the retrospective borrows its title, There’s something I must tell you (2013), records conversations between freedom fighters and their daughters and granddaughters, while It’s a pleasure to meet you (2016) and That particular morning (2019) see the descendants of assassinated activists sharing stories of inherited trauma. A journalistic sensibility—to bear witness, to disseminate, to resist, against all odds, the amnesia of the next-thing—is at work.

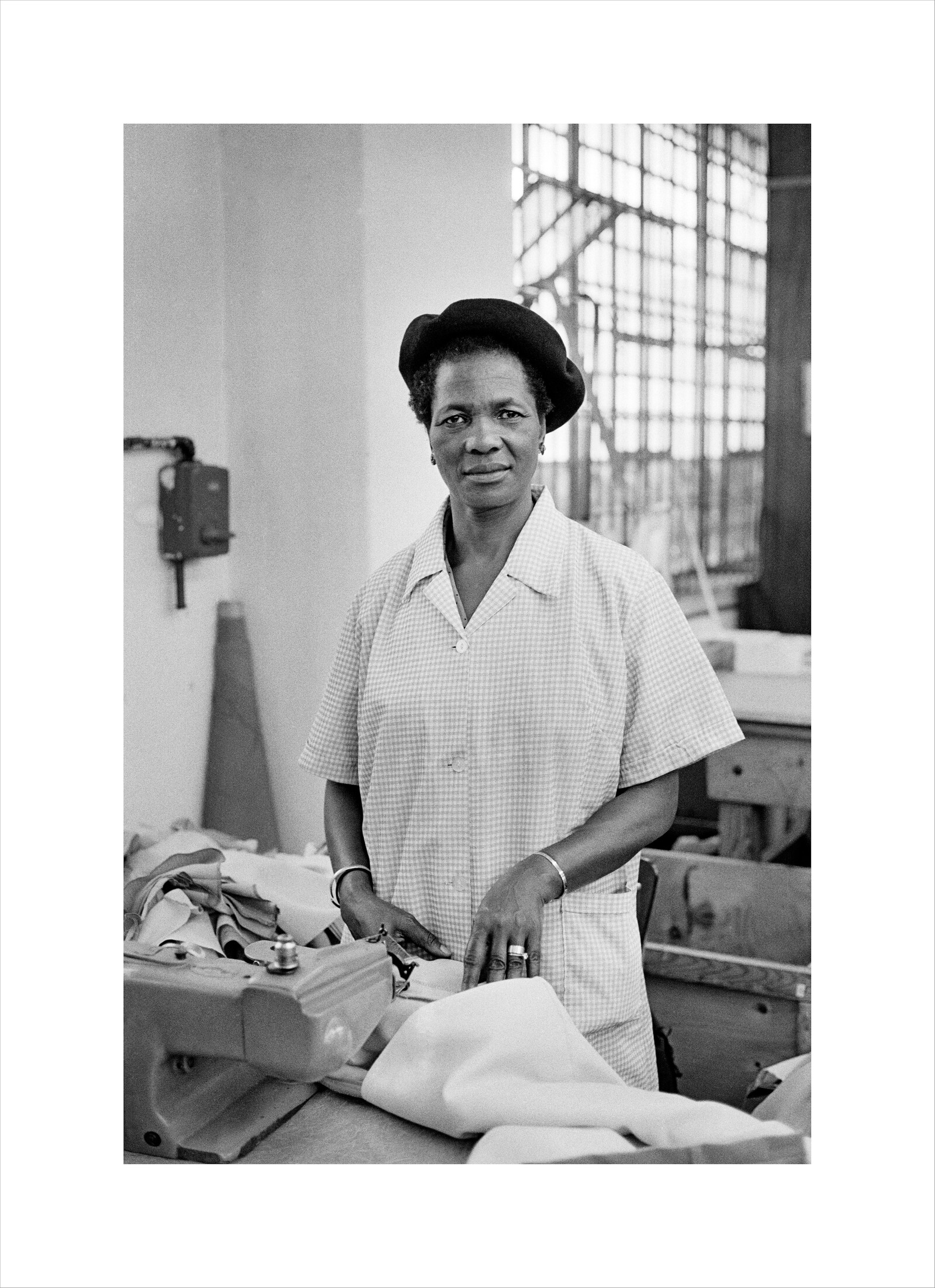

So too is the desire to attend to the quiet moments at the fringes of the struggle: not the committee meetings, but the conversations around the dinner table; not the protest, but the cups of coffee shared afterwards, the memories that persist after the spectacle has ended. This impulse is exemplified in the series “All Our Mothers.” Spanning the 1980s to now, Williamson’s photographs of women—activists, mainly, along with writers, artists, educators, and cultural workers—are staged at home. There’s Amina Cachalia, a founding member of the Federation of South African Women, pictured in front of the entrance to her home in Fordsburg, once in 1984 and again in 2012. There’s Caroline Motsoaledi—the wife of Elias Motsoaledi, one of the accused in the Rivonia trial who was imprisoned along with Nelson Mandela—beside her sewing machine in 1984, then at home in Soweto in 2012.

What happens to these women—their faces, their voices—when they are transposed from home to museum? Can an artist’s name shepherd those of her comrades into the popular consciousness? Or does the lionization of the individual artist run the risk of eclipsing her collaborators’ work? Whiteness is the elephant in the room here. One of the most moving works in the show is For Thirty Years Next to His Heart (1990), which consists of forty-nine photocopies of a passbook belonging to Mr. Ngithando John Ngesi, which documents, in harrowing detail, the state’s surveillance of his movements. At the press preview, Williamson spoke about the ludicrousness of having to sign one such passbook for an employee of hers—a banal cruelty that she recognized, but in which she found herself nevertheless complicit. When the project was completed, Ngesi refused to take back his passbook. It was too painful. This pain is now on view for visitors to the national museum. Although the passbook was outlawed in 1986, the power dynamics at play, as this artwork journeyed from state to studio, from private collection to public institution, charge the piece.

This is, of course, not a phenomenon unique to Williamson’s work. But Williamson is the kind of artist who insists on the collision—who insists, moreover, on a shared public in a country that remains divided. “It’s going to take generations for us, for this country, to be absolutely free of the inhibitions that we’ve had and the difficulties that we’ve been through,” says the late Cachalia to her granddaughter Luiza in There’s something I must tell you. Williamson has proven that she is willing to work within the inhibitions, to face the difficulties. She has spent the last five decades and counting insisting upon the possibility, however fraught, of an us.

Apartheid-era legislation required Black South African men to carry identity documents—referred to as “passbooks” and derogatorily as “dompas” (literally, dumb pass)—that tracked their movements in and out of racially designated areas. Attempts to force women to carry passbooks were met with widespread protest, notably the 1956 anti-pass Women’s March to the Union Buildings in Pretoria, for which Silinga was a key figure.